This time of year is brutal for runners like me in the Midwest. My solution to the challenges of winter weather is to get a quality treadmill, hook up a TV, and distract yourself while getting miles in.

On shorter treadmill runs, I’ll watch documentary content; I have the ability to concentrate for about 45 minutes. But for anything longer, I need something mindless. I gravitate toward movies I’ve seen before to both distract and entertain.

Prepping to run 12 miles on the treadmill a couple of weekends ago, I didn’t plan ahead for my viewing choice. The first thing recommended for me in the Amazon video app was the movie Napoleon Dynamite. I clicked play and started my run.

But something happened the longer I watched. The running distraction left me completely focused on the film; I noticed the visuals and the nuances of the dialog. About two-thirds of the way through, I started to ask myself a peculiar question:

Is Napoleon Dynamite actually a brilliant movie?

I might say . . . yes? I spent the past couple of weeks thinking about this. While that’s far too long s time to linger on a pointless subject, I reached my conclusion. I’m not saying it was Academy Award worthy but Napoleon Dynamite was far more thoughtful than I ever gave it credit.

THE CHALLENGE OF GENRE

If I asked you to describe the type of movie Napoleon is, you’d likely quickly respond with, “dumb.” Try and determine where this movie fits and you’ll most likely group it with those “high school comedy” style of films. The 1990’s saw a revitalization of this genre, with Napoleon a slightly less-raunchy take on the 1980’s Porky’s-type movie. It’s a far take from another 2000’s high school flick American Pie.

In a way, the movies of Chris Farley and Adam Sandler were contemporaries of Napoleon, but most similar in my mind was Jack Black’s Nacho Libre; all mindless comedies that were a tad edgy but generally wholesome. Kids could watch these movies with their parents without experiencing awkwardness.

Ultimately, since Napoleon Dynamite belongs to this family of movies, we tend not to think deeply about it. In no way would we consider it art.

THE EMPHASIS ON VISUAL

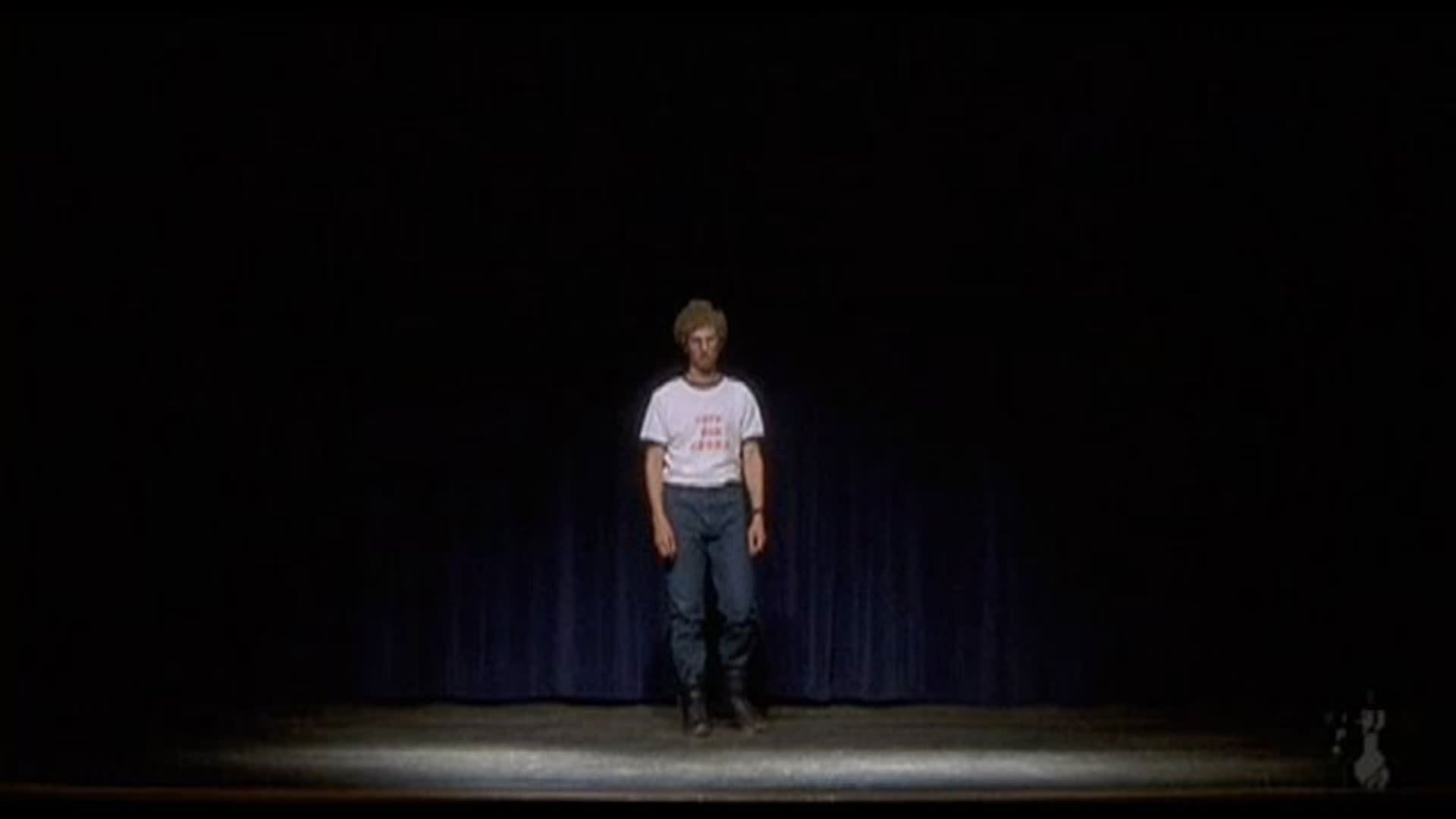

Watching this movie on the treadmill (with subtitles on, by the way), I was surprised that I was actually pulled in by the visuals. The cinematography is subtly captivating. They take a dated Idaho town and find a way to make it look retro-chic. A few examples of how they framed scenes illustrates this:

Even the color palette was well thought-out. This is something conspicuously absent from other frat comedies—thoughtful framing. The effort already places Napoleon ahead of its contemporaries.

THE SUSPENSION OF TIME

Think about when this movie takes place. It’s hard to tell. Everything seems dated—from technology to homes to vehicles. Songs played at the school dance are from the mid-80’s and the fashion couldn’t be much older than the early 90’s. If you’re too young to recall, DVD’s, CD’s and cell phones were prevalent by the end millennium, but the movie showcases VCR’s, cassettes, and pay phones.

But there’s a clue during the talent portion of the presidential speech near the end of the movie. The ladies of the Happy Hands Club dance to the Backstreet Boys song “Larger then Life.” This album was released in 1999. All the above signifiers predate the boy band tune.

In essence, the era of Napoleon Dynamite is the land that time forgot. This little town in Idaho is far behind the times and this is actually a plot point providing meaning.

THE COMMENTARY ON RACE

I’m convinced that this film . . . this means something. This is important.

There are some obvious themes woven into the narrative. We’re urged to make the most of each moment, exemplified in Napoleon’s love life and his final dance; when juxtaposed against Uncle Rico’s desire to go back in time, it’s clear you need to go for it. The idea of belonging looms large as well; this was one of those first “geek will inherit the earth” projects, but since the culmination is a peculiar dance rather than an inspirational speech, it’s a more organic triumph.

Yet even if it was unintentional, the movie speaks loudly about issues of race.

The town is obviously backwards, this dated culture symbolizing the people themselves. The film shines a light on the sometimes silliness of white, rural culture.

In this viewing, I finally noticed the low-key racism projected onto Pedro. Nearly ever interaction that the principal has with/surrounding Pedro involves prejudice: the administrator drops a “Juarez” reference on the young Mexican. In another scene, he derides Pedro for the inappropriateness of using a piñata that looks like Summer, his competitor. Still later, when Summer makes a chimichanga reference about Pedro in front of the whole student body, the principal ignores the racially charged comment.

In running for school president, Pedro is essentially confronting the town’s racism. Of course he isn’t cool, but he also isn’t white. Napoleon, then, serves as a bridge to move the town to the other side. His odd dance forces the rest of the students look in the mirror. He exposes their demented Caucasian caste system (where even the white alphas are lame [see: “Larger Than Life”]) so why shouldn’t it be destroyed?

More subtle is the relationship between Napoleon’s brother, Kip, and his internet girlfriend, LaFawnduh. While LaFawnduh might be the only African American in the entire movie, she is actually the only normal person in the entire movie (if you can excuse her interest in Kip). In the end, the only way for Kip to become normal is to leave town and join LaFawnduh in Detroit.

The town needs to grow. While Napoleon is a simpleton, he won’t discriminate.

So is Napoleon Dynamite actually a brilliant movie?

Maybe not. But at the very least, it was far more intentional than I ever would have believed.